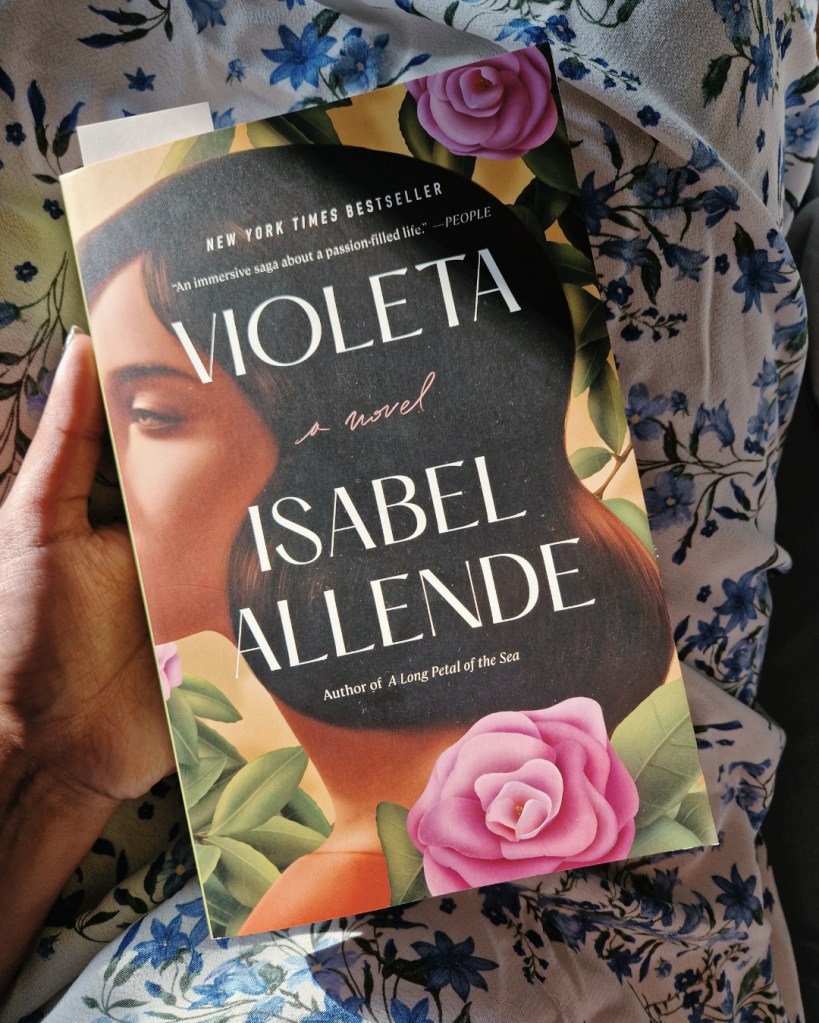

Earlier this year, I read A Long Petal of The Sea by Isabel Allende and I was convinced that it would be the best book I read this year and next year and the year after…you get it. But with Violeta, Allende has tested my choice and my taste and it is safe to say that I am stunned in every way possible by this breathtaking tale.

In this epistolary novel, Violeta recounts 100 years of her life to a man named Camilo (what his relationship is to Violeta is something I cannot give away). It is 1920, and Violeta is born in a South American country Allende has left unnamed. The world is recovering from The Great War and tackling the Spanish Flu in all its intensity. Amidst cautionary measures we are all too familiar with, Violeta begins developing into a vociferous and spoilt child, so much so that a governess from England is sent for. The Great Depression follows soon after and the devastation of this moment in world history sees Violeta’s family exiled to the far end of the continent, among vast, dry deserts and irrelevant villages.

Here Violeta is suddenly tamed and she flourishes, through many a trauma and triumph. When Violeta is in her twenties, a military coup ravages the country but she remains an apolitical observer to the destruction. A few more coups, a dictatorship, the Second World War and endless domestic turmoil, however, forces Violeta out of her oblivion. She watches loved ones come and go, and she experiences pain unknown to many of us. She enjoys passionate love – romantic and platonic. She forgives and forgets and regrets, but most importantly, she perseveres. And in the most poetic way, her life comes a full circle when, near death, she is trapped in her house because of the coronavirus and cannot truly say goodbye to the world that has been so kind yet so cruel to her.

Allende has created an iconic female protagonist through Violeta. She is fearless in her femininity, which was rare but not alien in the mid-1900s. She only moves forward, the consequences of her actions often only an afterthought. Violeta is also flawed in ways that don’t feel fictional; within her and within her aunts, companions and children, you will see women you know or have known, and evolution of womanhood through generations will feel deeply personal.

Allende’s storytelling in Violeta in this century-spanning saga will engulf you with such grandeur that it will, quite literally, alter your brain chemistry, as they say these days. There is an elegance in her prose that makes the most mundane moments of Violeta’s life seem exhilarating; the fervour with which she lives every single day of her long life, awe-inspiring.

Allende also delves into the intense political complexities prevalent in South America at the time and the lives of common people in its aftermath, and in spite of the heaviness surrounding these topics, Allende is careful not to burden you too much or take the spotlight away from Violeta’s life.

While this book is perhaps not one for those uninterested in the chronological retelling of history, if you harbour any interest in reading about a diverse, nuanced range of characters that represent human nature exceptionally well, Violeta needs to find a place on your reading list. That’s about everything I will say for now.