I met Mike when I first started attending PubSci – an enthusiastic, welcoming persona waiting by the entrance, ready to greet you, cross your name off a list, and direct you to the best seat in the house. What I didn’t know at the time was that Mike was a proficient science communicator himself, with extensive experience using various media to bring science to the public, particularly through science photography. After a deep dive into Mike’s work, I decided that I just had to interview him, even if for just one reason: he’s insanely cool. And that he’s a science communicator.

Currently Media Relations Officer at University College London, Mike has had every science communication experience possible – from writing newsletters for the American Physical Society to reporting science directly from the US Antarctic Program to hosting Resonance FM’s new radio show, The Science Show, with none other than Richard Marshall.

For this interview, I sat down with Mike to learn more about his wide-ranging experiences communicating science and to hear his one piece of advice for anyone hoping to share science with others.

Tell me a little bit about yourself and how you became a science communicator. Was it something that you have always carved out for yourself, or did it just happen over the course of your career?

I got there through a little bit of a circuitous path. I have always liked science, but when I went to university, I studied journalism, and it wasn’t really focused on science or science communication at the time. I was also able to enrol in an applied physics minor, and that appealed to me a great deal. After I graduated, I got an internship at a physics organisation that needed someone to do outreach and communications and that eventually turned into a job.

That’s how I got started. Science communication wasn’t something I set out to do, but once I found my way into it, I enjoyed it immensely, and I have stuck with it.

You were a part of the US Antarctic Program as a staff journalist, photographer, and podcast producer. What was that experience like?

The experience itself was huge because it’s a big, dynamic programme. One of the things that really appealed to me was that there was a wide range of scientific research happening, and I had the opportunity to ask the researchers the right kind of questions to understand their work and then write about it.

The other thing was that when you’re working in a research station like that, there are very limited resources. So, you have to be very resourceful about a lot of different things and build a lot of flexibility into plans. For example, the weather out there is very unforgiving, and you need to have a plan B, which also might not work and you keep going down that line for a bit.

At the same time, you’re living in dorms and eating in cafeterias together. The whole experience was a little bit like a national laboratory meets a mining town meets a college.

Do you have a particular highlight from your time there?

One of my favourite moments or trips was out to a place called Shackleton Glacier, where a field camp was set up for a couple of seasons for some palaeontology research and I was able to go out there with the team to take photographs and shoot some video. And we were the only human beings for nearly 200 miles. So, it was a very remote area. It was wild to think how few people had been to this spot and just how empty the vast landscape was. And amidst that, there was this research effort that was able to do what it needed to, pack up and go home.

Is it something you would do again – perhaps in a different locale?

There are two aspects to that.

I’d love to go to because I love to travel, so I would love to go see deserts, mountains, rainforests. I also like going there and being with researchers because it’s very meaningful to be able to kind of go and see this kind of thing.

What was difficult about the Antarctic deployments was that they’re very long. I would be deployed for about four months at a time and that’s very difficult personally. You’re away from your family and the Antarctic summers are over the Christmas period, so I missed a bunch of Christmases and things like that at home. And it’s very difficult on family and friend relationships to be gone for so long, especially in such a remote place with limited communication.

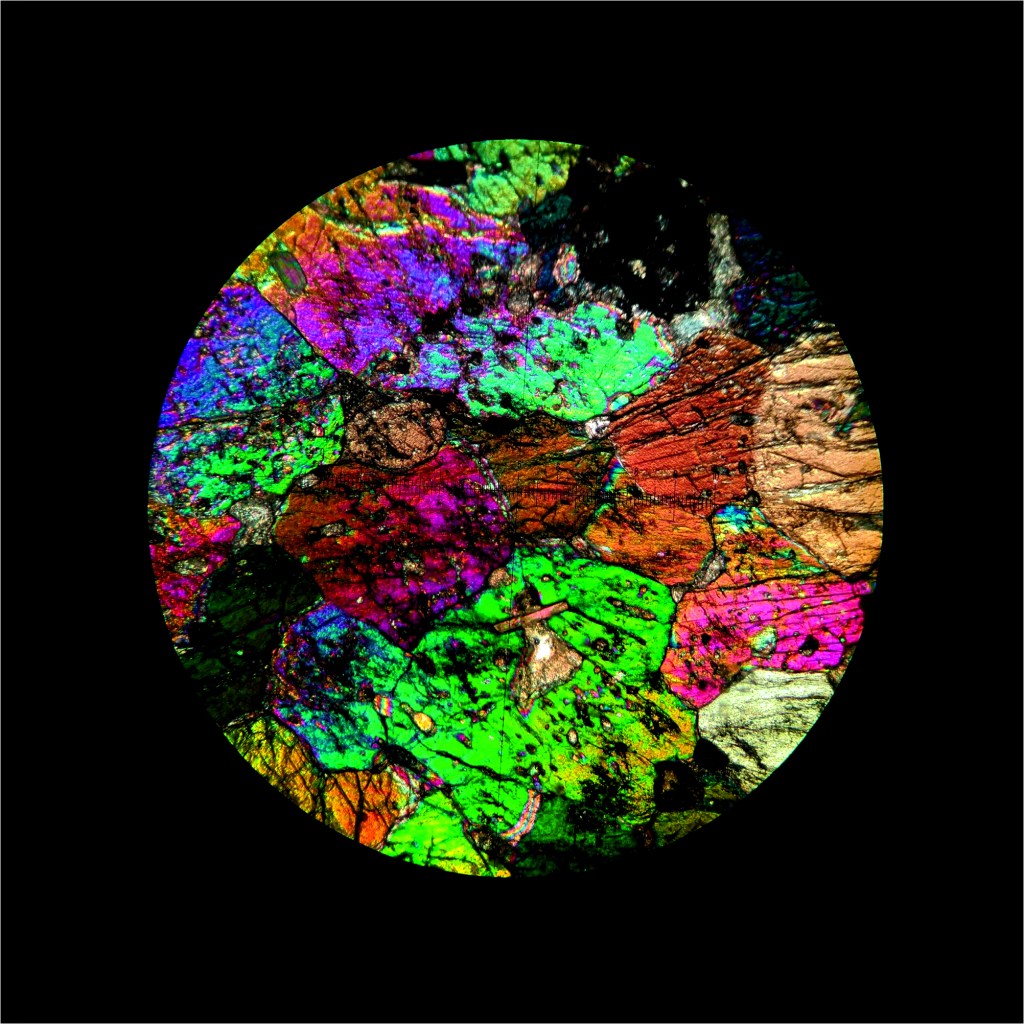

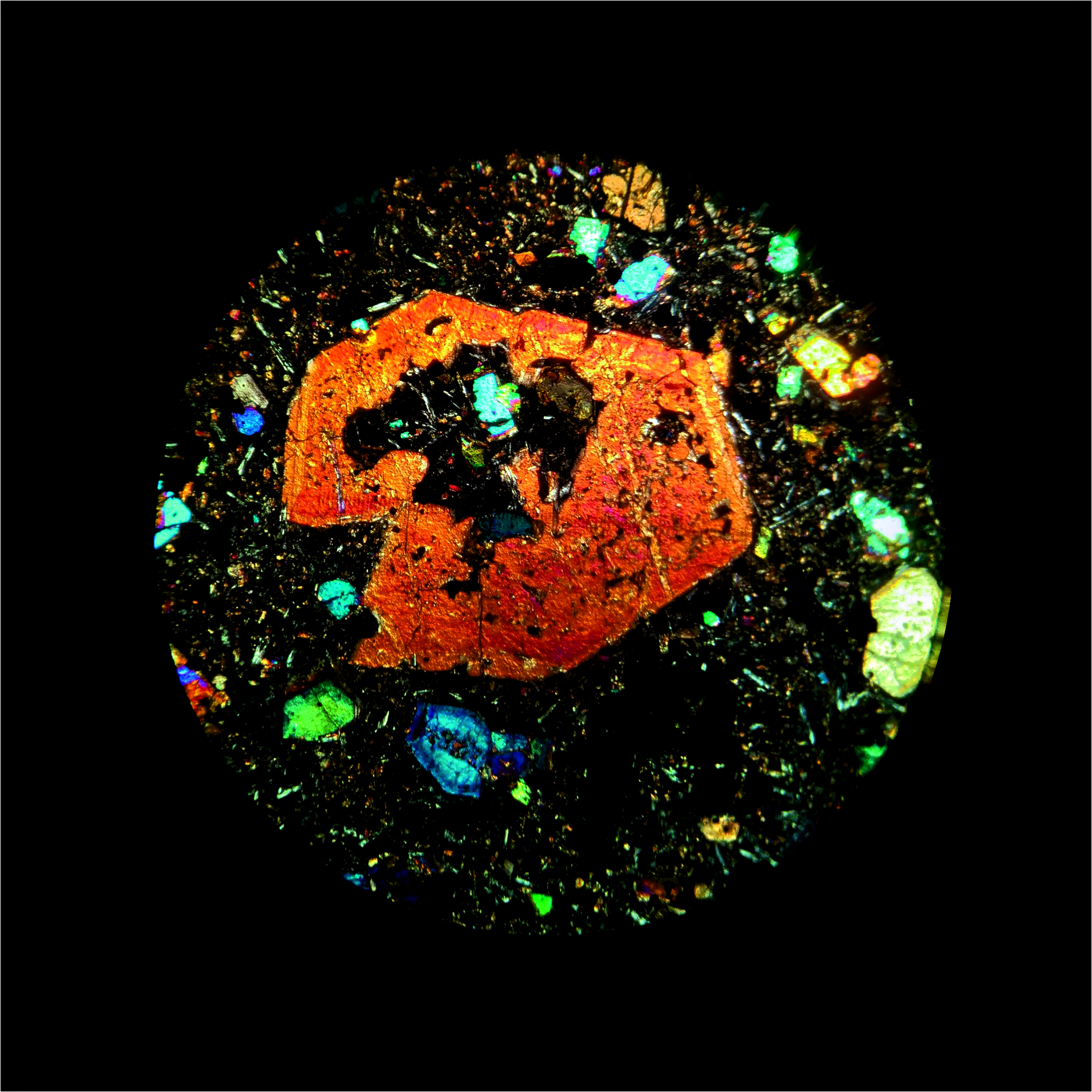

You have shared the photos from your US Antarctic Program work extensively on your website, along with other photography. I wanted to ask, do you think photography is an effective medium of science communication?

I don’t say this to be a generalist, but what I like to do is not just focus on photography, or writing, or podcasts – instead, I like to tie them together. I think that’s really important for storytelling. They’re each different tools for different aspects of scientific storytelling.

Photography in the Antarctic tells you a good story of people working in dramatic landscapes in a harsh environment to do science. At the same time, it’s also very humanising. The people doing the research are like many of us, and a diverse group as well. It’s good to be able to show that anybody can do science. Science is something that can happen to anybody. Science photography is a good way to do that.

Writing is just as important to show what research is happening, what research tax dollars are being spent on. Podcasts and radio shows are good for telling a story and further humanising things, where you can delve a little bit deeper into what researchers do and what their experiences are like. Someone once half-jokingly said that radio is a visual medium, but it’s true; when you hear a podcast or a radio program, you can create images in your mind that can make something seem so much more real.

Speaking of varied media, you have noted that you are always looking for different ways to bring the excitement of science and research to diverse audiences. What does diverse mean in this context?

There is a very traditional view of science as being done by old white men. In my experience, working with scientists is anything but that. Some of the best research in the world is being done by women, non-binary individuals, people of all ethnicities and backgrounds. And that is very important to show and communicate. Science is a very diverse field, with people from so many different parts of the world contributing something.

That’s the remarkable thing, too, if you kind of step back and look at it, science is this field where more so than almost anything else, different people from around the world can put differences aside and work together on projects and that kind of thing in a lot of ways.

That’s something you see a lot of in the Antarctic programs, where there are national stations, but there’s a lot of collaboration happening. And then if there’s an emergency, any pretence of differences in national politics is dropped and people just run to help people when they need it.

“Science is this field where more so than almost anything else, different people from around the world can put differences aside and work together on projects.”

MIke lucibella

You also media train scientists and researchers – why do you think it’s important for them to speak to the media? And when you are standing in a room full of scientists, what is one thing you always tell them?

It’s imperative for scientists to talk to the media because there’s an inherent kind of credibility that a researcher is given. These are people who are experts in their subject, people who have devoted their lives to understanding the ins and outs of a very particular topic. And there is a level of credibility that’s afforded to them. That level of credibility can make a big difference in policy spheres and understanding of the world.

They also have to be able to speak to the media well. It’s important for researchers to communicate the significance of what they’re doing and why they’re doing it, for a range of reasons. It’s to inspire people to do more science, to understand the world around them, and also to effect change.

There’s a lot of research being done to make the world a better place. And this needs to be broadcast. So, helping scientists broadcast their messages and their findings is necessary to effect that change.

To the second part of your question: I think at the core, the number one thing is to think about and empathise with the audience, and try to put oneself in the place of the audience. Presume that you are speaking to intelligent people, but they may not have spent as much time as you studying that particular subject. Your audience wants to know, wants to understand – but you have to help them get there. So, take a step back from what you know and your background in the subject, and instead go to what is an easy entry point to the topic and how you can describe your findings.

Going back to the topic of science communication, you have worked in science stand-up comedy, podcast, radio, photography and writing. Is there a medium you haven’t worked with yet that you would like to?

I mean, I would love to be a movie star!

I have done a little bit with filming and video, but not a whole lot. It is a very powerful medium, but it’s one that takes a lot of resources to do. I would love to be able to be part of a big team working on a science TV show or documentary and helping to shape it and tell a story that way. That seems like something that would be a lot of fun.

There is other stuff out there that I haven’t really considered, so I’m always keeping an eye out for future opportunities as they show up.

And your favourite medium so far has been?

I really enjoy photography on a level that’s different than most of the other kinds of stuff. Photography is a lot of fun because it’s very versatile. You can do anything from taking vast landscape images to tiny images of an insect or a spider. And I really appreciate that. It’s also a very good excuse to go out and find something interesting to take a picture of. That’s always something that I’ve enjoyed, the combination – being able to put the exploration side of science with the communication side of photography together.

For more about Mike and his work in photography and science communication, visit https://www.mikelucibella.com/.